Welcome to Part Two of Talking Human Rights’ special series, Palestinian Gandhi on Trial with our guest, Issa Amro.

Issa has been called the Gandhi of Palestine for his work promoting and organizing strategic non-violent resistance among Palestinians, Israelis, and their allies all over the world — non-violent resistance aimed at ending the military occupation of the West Bank and of the city of Hebron, where he lives. Issa has also been identified as a “targeted activist” as early as 2010, and in the intervening decade this targeting has only intensified. As of today, he finds himself facing trial before two courts – before an Israeli military court and before a Palestinian Authority court.

In Part One, we began laying out the context of these cases and talking about the military occupation of the West Bank in general. Check out that episode and our accompanying materials here.

In Part Two, we will learn more about Issa’s history as an activist and will delve more deeply into the context of the city of Hebron where he lives and works. Hebron is strikingly beautiful, though much of its beauty is covered in checkpoints, watchtowers, and movement barriers that people call “closures.” It has been called a “ghost town,” as thousands of people have been forcibly evacuated by the overwhelming Israeli military presence, and thousands more have left of their own accord, no longer able to make a life in the city.

Below you will find transcripts of this episode, edited and accompanied with photos and some additional resources to aid in your understanding. Thanks for being with us!

Resources/Transcripts

If you listened to Episode One, and looked at our materials, you have already learned a lot about the occupation of the West Bank in general. But something really important to understand is that, even though the whole West Bank is under military occupation, it is not all under occupation in the same way. It changes depending on where you go.

For instance, if you travel around the rural areas of the West Bank, which is to say, most of the West Bank, you are traveling in what is called Area C.

In Area C, you will see a very direct form of occupation by which the Palestinians are directly overseen and controlled by the Israeli military, particularly when it comes to building things. If you are a Palestinian and you want to build a water line, or a school, or a house, you must first obtain a permit from the Israeli military. This is why you see so many people in this part of the West Bank living in tents…

You will also see people living in caves.

So, that’s one level of occupation. That’s Area C.

Then, you have the big cities like Ramallah and Bethlehem. These are called Area A.

In Area A, the occupation works differently. In Area A, you have what is called the Palestinian Authority. It is crucial to not overstate the power of the Palestinian Authority, and crucial to understand that the PA is not a government, but is more of a local administrator that exists within the occupation and is required to cooperate with the occupation. But still, it does employ Palestinians to provide some local administration, even while under occupation, and it does provide something of a buffer. So when you go to these big cities, you don’t tend to see so much Israeli military infrastructure and you don’t tend to see Israeli settlers.

But Hebron is different.

Hebron is in fact divided into two levels of occupation, but the part of the city that we are concerned with, which you will hear us refer to as the “Old City,” or the “Old Town,” and also as “H-2,” for “Hebron-2,” that part of the city is under direct and intense military occupation…

Here is Issa describing what that’s like:

Issa: Hebron is almost a military area… Soldiers on rooftops, checkpoints, closures, settlers with guns, cameras for the army. So you feel like you are on a military base. Completely restricted, full of soldiers, full of settlers, full of guns, full of weapons. Your kids will see guns 24/7. You will hear shooting. You will hear soldiers training in your own city. Maybe they come to your house to have a training — on your house, on you. You will be a training object for the soldiers. That is life in Hebron.

Heather: First thing I want to say is, Issa is not exaggerating for effect. In Hebron, everywhere you go, you will see soldiers…

You will see them pouring in through through the doors of people’s apartments, marching up their stairs, and emerging onto their rooftops.

You will also see that the soldiers have built quite a few watchtowers on said rooftops.

If the family goes up to their rooftop, the soldiers can say, “You must leave. This is a closed military zone. Your rooftop is a closed military zone.” [Note: We will discuss the military law that allows this in Episode Three.]

In Hebron, you see entire city blocks closed off by gates, closed off with other barriers, totally emptied out, filling with trash and debris.

You see block after block of shops that have been closed, their doors welded shut, all part of the army’s ongoing effort to evacuate huge parts of the city.

People call Hebron a ghost town…

It’s quite shocking and scary, and it’s a lot to get your arms around. Your first thought would be, naturally, that it looks like a war zone…

You might think, “This must be what war is like.”

But Hebron is not a war zone. There is only one army here, an occupying army, and then there are the thousands of people just living their lives, or trying to live their lives.

It would be an oversight to not mention that Hebron is still quite beautiful… It is full of pretty pathways…

(Note: This area has been restored by an organization called the Hebron Rehabilitation Committee, which has rehabilitated buildings and public areas all over the city in an effort to bring the town back to life.)

…Hebron is full of beautiful buildings…

Hebron has an old souk where the streets narrow and everyone must pass on foot, though most of the shops are, again, cleared out, their doors welded shut…

Hebron is also quite spiritually significant. If you were to visit Hebron, you would certainly be taken to this structure:

This building, which dates back to the time of Herod the Great, and which has been built and rebuilt and added to many times since, is called the Ibrahimi mosque by the Palestinians. It is called the Cave of the Patriarchs by the Israelis.

But what everyone in Hebron seems to agree on is that under this building, protected by its walls, is a cave that is written about in the book of Genesis. It is the cave of Machpelach. And this cave is said to be the place that Abraham and his wife Sarah, and sons Jacob and Isaac, and their sons’ wives Rebecca and Leah, are buried.

Finally, in introducing Hebron, we cannot neglect to introduce the settlers of Hebron, as the presence of Israeli settlers in this city is key to understanding why the city is like this, why it is under such brutal occupation.

You don’t usually see settlers in the middle of Palestinian cities. You usually see settlers in the countryside, in Area C, where the Israeli military exerts complete control and where the settlers can feel protected. If you go to a big Israeli settlement located in Area C, the military’s ability to dominate this area, and to clear this area for the settlers, can make it feel like you are hardly in a settlement at all. So, most Israeli settlers will move to these settlements.

But the settlers of Hebron are a very small, very radical, group who have decided that they would not like to live in a settlement in Area C, but rather that they must live in the heart of the largest Palestinian city in the West Bank, in the city of Hebron. In fact, they have defied their own government and military several times in order to do so.

This group of settlers first came to the city in 1968 right after the military occupation of the West Bank began. They disguised themselves as tourists coming to Hebron to celebrate Passover; they rented rooms in a local Palestinian hotel; and then, when Passover was over, they refused to leave. They had to be dragged out, in fact, by the Israeli military. They proceeded to sneak in again, and be dragged out again, and even to this day they find themselves being dragged out of Palestinian-owned buildings by their own military.

But over the years, the settlers of Hebron have been able to establish a few settlements within the city and that is why there are so many soldiers there, thousands of soldiers, to protect them and clear the way for them.

If you travel to Hebron, you will have no trouble finding a settler to tell you these stories. To the settlers, it is a source of pride to have defied their own government, and to have pushed their own government continually to allow, little by little, their presence to take hold in the city. They are very effective activists.

So, these are the things you will learn and see walking around in Hebron and you should know them before listening to our interview, so it just makes better sense to you.

Heather: Issa, a question I have always wanted to ask you is, When did you first become politically conscious? I have been wondering if the First Intifada and all of its non-violent organizing had an impact on you?

Issa: I don’t remember anything about the First Intifada… I remember women mobilizing protests, people having strikes, closing the shops, closing the streets, [but I don’t remember much more], because my family wanted me to be a good student, and I was studying hard in school, and getting very good marks for my studying.

The first milestone of my life was the Ibrahimi Mosque Massacre when Baruch Goldstein went into the mosque and killed 29 Palestinians. I was blocked from going to school for three months because of the massacre. We lost two students from my school, who were killed by Baruch Goldstein, and one of them was playing soccer with us every morning.

Heather: For listeners who may not be aware, I want to make sure that people know that when we are talking about the Ibrahimi Mosque massacre, we are talking about a massacre perpetrated by an Israeli settler, who, in 1994, disguised himself as an Israeli soldier, and snuck into the Ibrahimi mosque during Friday prayers and killed, as Issa says, 29 Palestinian worshippers. It’s important for American listeners to know that Baruch Goldstein was born an American, radicalized in America, by a radical American rabbi named Meir Kahane, who himself founded an extremist political movement that was banned by the Israeli parliament and designated by the US government as a terrorist organization. But back to you, Issa, I’m sorry, please tell us more what happened after the massacre.

Issa: It was Friday morning and all Hebron was shouting and screaming about what happened and all the people were asking each other to go and volunteer blood. And people were very, very angry about what happened. And the reaction of the army was very violent and around six people were killed outside the mosque. Twenty-nine Palestinians were killed inside the mosque by Baruch Goldstein and six people were killed outside by the soldiers. And people were trying to take their relatives from the hospital to bury them in the cemeteries, because they were afraid the soldiers may take the bodies.

Heather: And the soldiers put you under curfew after the massacre, didn’t they, for…was it three months?

Issa: After the Ibrahimi mosque massacre I didn’t go to my school for three months. The area of my school was closed for three months, because of an Israeli American fanatic extremist Kahanist who went into the mosque and killed the Palestinians in the mosque. We were killed, we were the victims, and we paid the price for that.

Heather: And can you tell us what a curfew is?

Issa: It means you are not allowed to leave the house. Every few days, they give you one hour, two hours to go to do some kind of shopping, but you are not working, so from where you have money to do shopping? So they made people live in poverty, in spite that [the old city of Hebron] was the most crowded area of shops, full of people, full of shops, very expensive shops, and a very beautiful area. After the Ibrahimi mosque massacre, everything was closed and the closure was expanded after the second intifada.

Heather: What happened when you were finally able to leave your house again? When the curfew was finally lifted?

Issa: I went back to school. And I went back to see the closures, how the streets are divided, how Shuhada Street is closed, how shops are closed, how we have segregated roads, one for the settlers, one for the Palestinians. That left a huge amount of anger in me, because we were the victims of the massacre and we were punished because we are weaker, because we don’t have the same rights that the settlers have in our own city.

Heather: So while you were inside during the curfews, the army was changing the face of the city. Closing streets and shops. And you mentioned Shuhada Street, which, for people listening, is the main street of the city, that the soldiers took away from the Palestinians and reserved for use of the military and for the settlers. And I know you’ve spent so much activism trying to get this street reopened to Palestinians, just to be able to walk on it. But do you mind describing it a bit, what Shuhada Street was like when you were a kid?

Issa: Shuhada Street was the center of the city. It was our Times Square. Everybody coming to Hebron should go and visit Shuhada Street. It’s the connection between the south and north and south and eastern parts of the city. The main cemetery is there. The Ibrahimi mosque is there. The vegetable and fruits market was there. The wholesale market was there. The handmade market was around. The main bus station was on Shuhada Street. It was the heart of Hebron.

Now, Palestinians are not allowed to walk in the majority of the street. They are not allowed to drive anywhere in the street. We have around 1,800 shops closed in the street and around the street. Among them around 520 shops closed in Shuhada Street by military orders. We have around 1,000 Palestinian apartments that became empty, because many apartments are in Shuhada Street. Certain families use the back door to get into their homes, because the main doors are closed. I know a Palestinian family that uses a roof to get into the house. I don’t think life will come back to the Old City of Hebron without reopening Shuhada Street for the Palestinians.

Heather: It’s true, just walking around Hebron, it feels like someone came and killed not just the people living in the city, but the city itself.

Note: Here is a photo of Shuhada Street that you may remember from the introduction.

As you can see, there are barriers along the street that bar any traffic from entering Shuhada Street street. Any doors that open onto the street have also been sealed. This explains why a family that lives in an apartment on the street may have to enter through their rooftop, or through a side door if they have one.

And here is a photo of what it looks like when you live on a street that leads to Shuhada Street. Any street that leads to Shuhada street has been closed off.

If you want to learn more about the evacuation of Shuhada Street and the Old City, an excellent thing to do is to familiarize yourself with the organization Breaking the Silence, which was founded by Israeli soldiers who served in Hebron and who talk about their actions there in heartbreaking detail. You can find many videos of the soldier testimony on their website, or, if you travel to Israel/Palestine, you may even take a tour with them through the city.

Heather: I wonder if we can switch gears. I want to ask you about what your life was like during the Second Intifada, during the second Palestinian uprising against the occupation. I know that this time was filled with so much violence and repression, but my understanding is that it is also when you came into being as a non-violent activist. Can you tell us a little about that?

Issa: My family didn’t want me to participate in the Second Intifada. I was doing very well in university, studying very hard, sometimes studying 12 hours a day after university, to get my engineering degree. In the last year of my engineering degree, in the middle of the Second Intifada, I went to school and I found the way to my school closed. They [the soldiers] sealed the doors, they welded the gates, and they declared the campus as a closed military zone.

For me, it was a very hard moment, because it was my last semester and it was my life. And I went home very angry, I was every crying about it. But it was not about the occupation. It was not about human rights violations. It was about me, it was only about Issa studying very hard for four years and a half and I chose to study inside of Palestine not outside of Palestine so I could stay close to my family. And I chose my major, I liked it, I wanted to be an electric engineer. I wanted to do my postgraduate and get my PhD and go on in my educational track.

So I went home and I went to Yahoo, because Yahoo was the main famous search engine in those days. And I wrote “How to make a revolution?” For me, it was a revolution. I was lucky to get a lot of information about non-violent revolutions. I read a lot about Gandhi. I read a lot about the civil rights movement in the US, about Martin Luther King. I read about Mandela, and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. I read all of that and I went back to school and I told the students “Let’s fight the closure of our university.”

The first thing we did is we established a committee of seven students we were all in the engineering college and we started mobilizing Palestinians. I remember the first action that we did was closing the main street in Hebron for the Palestinians and everyone said “What is this? Are you crazy? You are closing the main street for the Palestinians! How will you affect the occupation?” And I told them “It is written in the books…to generate public opinion.”

And then we went to the governor, and to the mayor’s office, and told them you should come with us, or we’ll close your offices, too. To recruit them. Then we started our activities and actions and it took us six months to recruit the students and to convince the students. From one-to-one meetings, to group meetings, to recruiting the media and international activists who would come with us. And then, we occupied the campus with a few thousands students, and we won. And winning that big victory made me think that I could use non-violence to get rid of the occupation.

Heather: And again, you were under curfew for much of this time, organizing the students, and you weren’t supposed to leave your house or do anything like what you were doing.

Issa: It was the Second Intifada and we had tanks all over the streets. And this is why I said, okay, it must be peaceful. It was a tactic for me in the beginning, and I said, Okay, let’s just try. And we were hiding the brochures, we were hiding the press releases, we were meeting in secret places, we were not using the phones. We were really careful as a group of organizers not to be caught for what we were doing, because it’s illegal. Even organizing peaceful, non-violent campaigning for the students to reopen their university, it’s illegal.

Heather: Do you ever seen any of those guys, your fellow students who you organized with?

Issa: Yes, we see each other and we are very proud of that time to reopen the university and work against the closure of our university. And now we are more aware of what we were doing. At that time, we were not aware.

Heather: So what happens next. You get the university reopened, which is extremely impressive. They what happens?

Issa: I graduated, I got my degree with very good marks, and I became addicted to non-violence resistance. So I established the International Solidarity Movement in Hebron to fight the wall around the city and around the villages. I started organizing people in South Mount Hebron. We managed to bring back Gab Awis village.

Heather: Wow, I want to talk about Gab Awis, actually. So, for people listening, we’re talking here about Area C, the rural area that is most of the West Bank, where the Israeli military exerts direct occupation over the Palestinians and where you will see people living in tents and caves with no running water, no electricity, because they’re not allowed by the army to build that stuff. And I just want you to talk about this, Issa, for a couple of reasons: One, here you are, a Palestinian activist, and you go to resettle a village, but what you’re doing if I understand it is you’re actually helping to implement a decision of the Israeli high court. The court had already said that these villagers could live in this village, and it was the soldiers and settlers who wouldn’t let them stay, in defiance of the high court orders. So it makes me wonder is the high court something you can use…

Issa: Okay. My experience with the Israeli supreme court is that usually Palestinians lose, for many reasons. The first reason is that it costs a lot of money. And the judge is usually biased to the Israeli occupation and I see that the supreme court is part of the occupation and the Israeli institutions in general they are part of the occupation. They maintain the occupation in one way or another. But sometimes, we get some victories in the Israeli supreme court and in the beginning of my activism, in 2004, we got a call from one of the Palestinian villages saying that they won a supreme court decision to go back to their village and they are not able to implement it because whenever they go back to their village, the settlers attack them and the soldiers don’t protect them and dismiss them. So I went there, with an international presence. We slept there in the village with the families and the whole village was afraid, and they didn’t believe that we have power as non-violence activists. The settlers came and tried to attack us, but they found the cameras. They found activists speaking English and Hebrew and Arabic and talking with confrontation. They escaped the first night, the second night they tried to attack us again, they escaped.

But now [after several days of confrontation and efforts involving Palestinian, Israeli, and international activists] the family inhabits the village and they have one of the best NGOs in South Mount Hebron. It’s called Comet-ME, which is giving solar panels and renewable energy for the Palestinian families who are living all over South Mount Hebron. So you can say that they brought electricity to the people there and they are living in one of the houses where I slept in 2004. So it’s a big victory, but it’s not the case now. The supreme court is much more right-wing now, and the army is more right-wing, and the settlers feel more confident especially after all the green lights they have gotten from the Trump administration to do whatever they want and after the appointment of the new American ambassador to Israel who is supporting the settlements and he feels that he is part of the settlement community and he is very biased. [Note: Here, Issa is speaking of US Ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, who has said that Israel has the right to “annex” illegal settlements in the West Bank.]

Heather: That’s such an important thing for Americans to know, I think, the impact of what we do, who we elect, on your situation. But I want to talk more about this phase of your activism. Because I remember my first time going into the South Hebron Hills, Issa, hiking into an area where only one family lived in a cave in view of a settler outpost. And I remember how scary it was to be out there in this incredibly barren landscape that you can’t reach by car, that you can’t reach by trail, that you actually have to hide where you are going. I remember we arrived finally to the cave and it was pitch black…because, again, no electricity. So, tell us what it was like for you to go there in 2004.

Issa: It was the beginning of my activism so you can say I was afraid of soldiers. I was afraid of guns. I was afraid of settlers. And when the people from the village asked us to escort them to the village and stay with them, it was an impossible mission. It was not easy to go to darkness, to go to a place without a restroom, without electricity, so you are going to nowhere, knowing that Israeli settlers and soldiers with guns may attack you in the night. They may shoot you and nobody will know about it and you have no place to escape. So it was not easy for me to go.

But I usually go over my fear by saying that, you know, what I am doing is important and the outcome and the impact of the activities will be for years used by other human rights defenders. And now Gab Awis is fully inhabited and I am so proud of myself and the others who were with me. It’s the kind of action where anything is possible. Nothing is impossible for activists. You can do it. You just need to try and be brave and know that you are not alone. You have many supporters in the world and you are not a cheap target to the authorities. The authorities are afraid of you more than you are afraid of them.

Heather: So you really faced your fears, and it sounds like there was a real payoff.

Issa: I can say that that experience made me more brave. It gave me more courage to go over my darkness phobia, that the darkness will not stop me from doing anything. It gave me more courage to go over the phobia of the soldiers and the settlers. It was very important to me as Issa to do that action. It was really one of the best things I did in my life, to go over a lot of my weakness. You know, now I am much stronger, I would do it like that. But that time, I remember, it was a hard decision, and I didn’t sleep all the night. I was not able to sleep. I was not able… But now, I am much stronger, and I can do anything alone or with others like that.

Heather: Wow. That’s incredible and I have to ask you what it was like that first morning when you got up, of course, not having slept. I remember my first morning waking up in the South Hebron Hills, and just coming out of this cave, and it was so bright and so sunny, and everywhere you look it’s golden dust and sand as far as you can see. Just rolling hill after rolling hill. It’s so beautiful.

Issa: Yes, for sure, because in 2004 it was the beginning. Then, I went many times to sleep in the caves. I like the area a lot. I like the sunset, I like the sunrise, I like to hear the dogs in the night, I like to hear the birds in the morning, I like the life there. I like the sheep, I like to see the workers sneaking in through that area to go to work inside of Israel. So I think it is really amazing. It became a part of my life. It even became part of my satisfaction as a person to go, almost a sort of sightseeing for me now to go sleep in a cave in the middle of nowhere, you can say.

[Note: It is difficult to capture the vast, golden beauty of the South Hebron Hills in photographs, and to conceive of the life Palestinian farmers lead, often without access to running water or electricity. You may enjoy this photo essay by South Hebron Hills activist and prolific writer David Shulman. While you are at it, this is another excellent photo essay by David Shulman, in which a Palestinian farmer has received running water by the organization Comet-ME that Issa mentions.

And here is another very important photo essay from Mondoweiss, covering ongoing efforts of Palestinian, Israeli, and international activists to resettle villages in the South Hebron Hills.]

Heather: This story of you facing your fear is so interesting, because you’ve inspired so many people to be brave, and I think if anyone were to describe you, Issa, brave would probably be the first word they would use. And so, this is how you got brave, by doing something really scary and building your strength and meeting all these people who are also getting braver. And then you take this energy back to Hebron where I have to imagine people were pretty scared to follow you.

Issa: Yes, [after the South Hebron Hills], we decided to come back to the old city of Hebron and fight the apartheid policies. It was Palestinians, Israelis, and internationals working together to highlight the human rights violations, and then I said that I should establish a Palestinian group to recruit Palestinian youth to join the non-violent resistance, so we established a group called Youth Against the Settlements, and so from one campaign to another, we generated public opinion in Hebron and in the world about non-violent resistance in our own city and about the human rights violations and we managed to increase a lot of awareness of what was happening in the city. And we managed to give the Palestinians a tool, and even a culture, to document the human rights violations, to use the video camera.

In the beginning of distributing the cameras, it was impossible to give [them] to the people, because they were afraid to use [them], afraid that they will be a target, afraid that the army will punish them, that they will break the cameras, they will take the cameras, because the people in Palestine know that the army can do whatever they want. Under military law, you don’t have any rights, so we started convincing the women.

And the women listened to us, because we said this is a tool to defend your children, and to defend your husbands, and to defend your house. Then, in time, it became a culture and people react without any kind of mobilization with their smart phone cameras, with their own cameras, and they put it on-line and they send it to us to send it out, to use it for documentation, to use it for legal cases, for advocacy and for media, especially the international media.

Heather: That’s really incredible. And I know that this really caught on in the region, and that the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem ultimately called upon you to reproduce this project all over the West Bank, and so you trained people all over the West Bank to do the documentation work you started in Hebron. You actually won an international award for that work, the One World media award in 2009. And the accolades just keep coming in at this time and, not coincidentally, the monitoring of your activities by the authorities – the arrests, the detentions – also increase in this period. But I want to fast-forward to the year 2016, and to the event that is said to have been the last straw, the event where the Israeli military finally decided they would compile 18 charges against you going back to 2010. And that they would put you on trial. So, what were you doing at the time this all started, Issa, on that day in 2016?

Issa: We got a call from a Jewish community in the US and we got around 120 Jewish activists coming from the US to Palestine to participate in the non-violent resistance and they wanted to take part in one of the actions. We decided together to establish a cinema, the only cinema for 800,000 Palestinians in Hebron district. So we started doing it confidentially not to let the army know what we are doing in a Palestinian closed factory to protect it from the settlers and reverse it into a community center and a cinema. And we managed to surprise the army despite that they tried to stop us. Palestinians, Israelis, Americans, Muslims Christians, Jews, seculars, all people were together hand in hand and we were saying that occupation is not our Judaism, occupation is not our religion, and non-violence is our main method to end the Israeli occupation by strengthening the Palestinian civil society and the Palestinian people.

The occupation didn’t like that. The occupation declared the area a closed military zone. A few activists were arrested that day and after that they started my indictment with 18 military charges. So that was the year and that was the trigger for them to open 18 military charges and take me to court and collect all my charges from 2010 to 2016.

Heather: So, I wonder if you can talk a little about the state of the movement, which I know is not so good right now…

Issa: I can say that the movement right now is suffering from a shortage of activists, because you know to be an activist you pay a very high price. Me, I pay a very high price. I was attacked physically many times, I was arrested many times, many, many times detained, and many others activists they face the same. Attacks on them, attacks on their families, attacks on their friends, so if you are a non-violence activist — Israeli, international, or Palestinian — you pay a very high price. They deported many international activists, they prevent them from coming, they question them. You know, us, as peaceful activists, they are isolating us from the world, they are isolating us from our activist communities, they are isolating us from the international community and we became really a target and our friends became a target. You are not even allowed to criticize Israel now and they may consider you an anti-semite if you are criticizing human rights violations. If you are pro-Palestinian, pro-human rights, pro-peace, pro-justice, pro-equality, you will be labeled as an anti-semite, you will be labeled terrorist, you will be labeled as an anarchist, or an I-don’t-know-what. They find a label for you to disconnect you from your own community and disconnect you from influencing public opinion even in Israel or even in the US here.

Heather: So how do you get people to join you?

Issa: I try to talk to their morals, to their principles, and I tell them do you want to be a normal human being and no one mentions you in history? Or do you want to be a human rights defender? And be mentioned, and be heroes? And many people, you know, they want to be heroes. And I think Martin Luther King gave his life for his own people. And Mandela gave 30 years from his life in jail for his own people and me, personally, I want myself to be mentioned as a human rights defender. That’s all. There is no change without sacrifice.

And the price is high. We try to reduce it by bringing more international attention, and this is what we are wanting from the American audience who are listening now, to write to their Congress to support Palestinian rights, to write to the media, to talk to their communities, to come to Palestine and to see the situation to support Palestinian initiatives and projects on the ground, to protect human rights defenders by raising their voices and connecting them to other resources here in the states.

Heather: So people in the United States can do a lot here…

Issa: The moment we have hope that our resistance on the ground will be effective, many people will join us. So, if we have, for example, an American president supporting Palestinian rights, the American congress they understand our self-determination, that will encourage people to stand up, so you know, the hope will come from outside.

Me, personally, I am so moved now about the American young activists in the schools and in the campuses here in the universities and I think that the movement is growing here and that gives us hope. I hope the movement will be bigger all over the world, which will influence our work on the ground to recruit more Palestinians to join.

Heather: And what does it mean for the movement, that you have been targeted in this way, that you could go to jail for years?

Issa: I can say, if they target me more, it means that they know that I am influencing my people and this kind of work is really valuable, so I will keep doing it. Sometimes I am more careful than other times so that is taking into consideration not to give them any excuse or ammunition to put me in jail or put any other activists in jail.

Heather: But taking you out will impact the movement.

Issa: First of all, they will affect my fellow activists. I think non-violence will be less attractive to people and they will affect our non-violence movement in Palestine and the world by taking me in jail and isolating me and taking away all of my experience mobilizing and talking to the public.

Heather: And the toll this must take on you as a person, I just can’t imagine.

Issa: Me, I am very sad and disappointed for being indicted. I am very sad for going to court. I don’t feel well. I am very stressed. I can say that the last two, three years of my life were horrible, because I have nightmares to be in jail, I don’t want to go to jail. I thought that the Israeli occupation would not target me for my non-violent resistance. I was very careful and I was doing very well to incite my people to non-violence and talk to them in a language that non-violence is the best methodology to end the occupation. I am very proud of them now that it became a culture. It is a matter of time [before we have] a real massive mobilization.

The only problem now is our leadership and we need a stronger, young leadership to take us to civil disobedience. The occupation is afraid of that. For sure, the occupation will try to defend itself from me and from any kind of peaceful mobilization, so they are using all types of threats, all types of detentions, all types of indictments, they will try to put me in jail, and I think that putting me in jail means destroying my 15 years of work to increase the culture of non-violence, because many people see me as a hero for using this track for a long time and doing very well and I have a lot of winning and I have a lot of examples to tell people it’s working, it’s doing well, and we are doing well with this non-violence approach.

But the occupation and the supporters of the occupation don’t distinguish between a Palestinian who believes in non-violence or a Palestinian who believes in any other kind of resistance. They target the Palestinians because they are Palestinians. They target the Palestinians because they want to destroy their will to resist the occupation, even peacefully. And they target the Palestinians to make them sacrifice their rights and to accept to live as second or third-class citizens in their own country without any political rights and without even any basic human rights.

Heather: We’re going to wrap up this episode, and in the next episode, we’re going to talk more about the uneven legal system and the context that allows cases like the one launched against Issa to happen. We’ll talk about why people use the word “apartheid” to describe it. It’s such a hot-button word to use, but it’s really important to understand what is being referred to here, what this means. So that will be Episode Three.

But before we say goodbye to Episode Two, and because we focused so much on Hebron in this episode, I just want to end with where conversations often end up when you are talking to a Palestinian from Hebron. And that is, they end up at Shuhada Street, just talking about what it was, talking about its beauty, how much it meant to them, and just…mourning the loss. And I think it’s really beautiful and meaningful and it’s worth listening to. So…here we go:

Issa: I remember Hebron [before] all the closures. I remember Hebron when I used to wake up in the morning around 6AM to hear the shopkeepers, the vegetable market alive. They used to open [at sunrise] and I remember them calling to sell their potatoes, their tomatoes, and in the season of the watermelon, they start screaming, the shopkeepers and the vendors in the streets, about their vegetables, their fruits, their products, I know that market shop by shop.

I remember when I was a child I was moving around, playing around, cycling around. Not anymore. The shops are closed, the markets are closed, I am not allowed to walk there. I am not allowed to go to the house where I was born, which we own, and I see the settlers they have all of that.

And it’s not only the vegetable market or the fruit market or the second-hand market or the wholesale market. All markets were there. The carpenters market, the blacksmith market. I used to make my toys there, to go to the carpenters market, or to the blacksmiths. It was full of people and shops and workshops there and I remember the meat market, the chicken market, the birds market. I remember the camels market and it’s one of my favorites to go to see the camels in the morning to escape from my mother. I remember when I was four or five even and I would escape from the house to go see the camels or to go drink some milk we would call a special name and you get a really tasty fat milk that you get from the new mothers…

Heather: Is this camel’s milk?

Issa: Camel’s milk, cow’s milk, sheeps milk, goats milk, everything was there. The area where the settlers are now was the main shopping area for the West Bank. So crowded my father held my arm not to lose me. Not the souk. The souk is smaller than the open space [market] and when you want to do anything, you had to go there. To fix your shoes is there, to buy anything for your animal is there.

Heather: Even the bus station…

Issa: Even the bus station is there, and the doctors, the engineers, the offices, the fuel station, everything was closed. Go to Times Square. Look around and imagine the same crowds used to be in Shohada Street. Maybe if we used technology as it’s used now in Times Square, Shohada Street would be the same. Even more.

…many of the shopkeepers now are broke. I see them selling in the street now in spite that they use to have big shops. They didn’t have the capital to open other shops. Who had capital, they reopened shops somewhere else. But many of them lost their life business, and it’s a family business too.

Heather: And when you are walking in the neighborhood and you see all the horrible things that happened, do you still find it beautiful?

Issa: I used to be happy to be arrested, and to go into the jeep in that area of the city [where I cannot go] and to see it. I used to look out the windows when I am not blindfolded, and when I am blindfolded I would try to look out, to see, you know, the area where I am not allowed to be. I used to feel a little big excited to be in an Israeli military jeep or an Israeli police jeep to pass by that closed area. The same for me it used to be for me to transferred from Gush Etzion to the military court in Ofer, through Jerusalem, to see Jerusalem, too, where I am not allowed, as a Palestinian to be. This is why they blindfold me. And it’s a kind of harassment too, a kind of insulting you. You are handcuffed as a kind of controlling you and destroying your passion, to make you feel angry.

Heather: Do they take you to the bus station?

Issa: Sometimes they put me in the bus station and sometimes they take me to the Kiryat Arba police station.

Heather: Does it still look like the bus station you?

Issa: Yeah, I know it well, I know it by heart, I used to go over there. And I can say that it is still Palestinian architecture. They didn’t change how it looks! It is, it is a bus station.

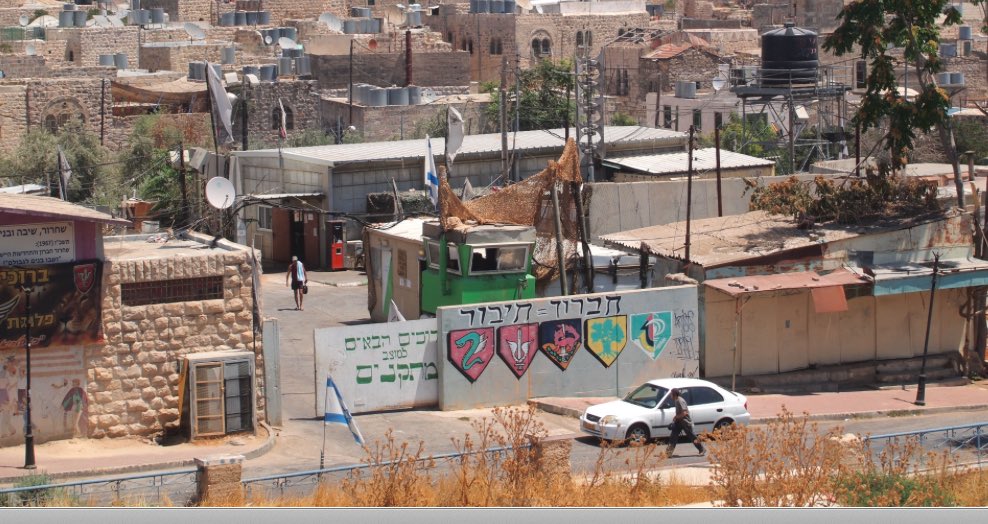

Heather: Okay, so that’s Issa Amro, activist extraordinaire, and that is Hebron. And just to explain that very last moment where Issa is talking about recognizing the bus station, I realize that we didn’t in the interview make it clear that when the soldiers shut down Shuhada Street, not only did they close down the markets and the city pool and all of that, but they also shut down the city’s main bus station and took it over as a military base.

Until next time, thanks for listening, thanks for being with us. This has been Talking Human Rights. This has been our special series, Palestinian Gandhi on Trial, Episode Two. I’m Heather Roberson Gaston. You can find us at the web at www.talkinghumanrights.com.

Note: Here’s a photo of that bus station.

In this Episode...

Heather Roberson Gaston

Talking Human Rights host and creator Heather Roberson Gaston is a writer, adviser, and educator in the field of human rights. She holds an undergraduate degree in Peace and Conflict Studies from the University of California at Berkeley; a Master’s in Human Rights from Columbia University; and a Certificate in the Advanced Study of Central and Eastern Europe from the Harriman Institute, also at Columbia University.

Heather co-authored Macedonia: What Does it Take to Stop a War? a graphic novel based on an early solo research trip to the Balkans as an undergraduate. She is now working on a narrative work exploring the many lives and deaths of the Israeli-Palestinian peace movement, for which she spent the better part of a year living and working in Israel and the West Bank.

Issa Amro

Issa Amro is a lead non-violence activist who lives and works in the city of Hebron, Palestine. Issa has championed non-violent struggle since the Second Intifada when he found his university shuttered by the occupying Israeli military. This closure prompted Issa to organize his fellow students, as well as like-minded Israelis, until the university was reopened and the students were able to return to school.

Issa has been named a top human rights defender by more organizations than we can count. He has organized his local community for the past fifteen years, and has spoken all over the world about the importance of non-violent struggle and about non-violent tactics. You can find him on Twitter where his handle is @Issaamro.